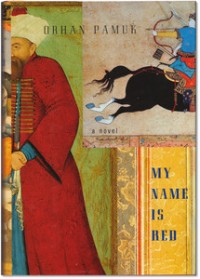

Title: My Name Is Red (Turkish – Benim Adım Kırmızı)

Title: My Name Is Red (Turkish – Benim Adım Kırmızı)

Author: Orhan Pamuk (Translator – Erdağ M. Göknar)

Year: 1998

Publisher: Knopf

Date Read: February 28, 2013

Goodreads Rating: ~ 7.5 / 10

My Rating: 6.5 / 10

In my analysis on the influence of translators in my previous post, I neglected to mention the work done by Erdağ M. Göknar in translating Orhan Pamuk’s (1952 – ) novel My Name Is Red. Not only did Göknar face the task of reworking the original Turkish text into English, he also had to maintain the style of the novel and make it accessible to a Western audience. The translated work made Pamuk a significant contender to become a Nobel Laureate which he achieved in 2006, a true testimony to the influence of good translating.

Interestingly, the notion of conflicting ideologies between the East and West is a central theme in the novel. Based in the 16th-century Ottoman Empire, a group of miniaturists are faced with the daunting task of creating a piece that satisfies the religious tendencies of Eastern art with the realistic portrayals in those of the West. The notion of depicting characters and scenes as they truly appear is taboo in the culture that the novel is based in, and the growing tension results in murder, conspiracy, and secrecy. Pamuk also manages to interweave a love story within the confines of the novel through a fantastic use of multiple perspectives.

The use of several different perspectives is something that I’ve always admired in lengthy novels, with Stephen King and Harry Turtledove being my two favorites that have mastered this method of storytelling. However, I put a certain emphasis that I enjoy this in lengthy novels. My Name Is Red is about 400 pages long, making it just too short for this style to reach its most effective state, in my opinion. Using multiple perspectives, especially in the case of this novel’s use of 19 narrators spanning 59 chapters, allows for a diverse look into the different intricacies of the plot. Simultaneous events can easily be described, unique thoughts can be elaborated on, and crucial accounts can be highlighted. However, if the novel is too short, as I believe the case of this one to be, the use of many perspectives crowds the flow of the plot and forces too much into too little space.

All of that being said, Pamuk creates a plethora of enjoyable angles to view the plot unfold. Most of such outlooks are through the eyes of the human characters, but occasional exceptions are made for illustrations, objects, and ideas to be able to speak. In a sense, the “fly on the wall” that would usually be ignored is given the opportunity to reveal things that may have otherwise gone unnoticed. Also, the naming convention for the miniaturists (Elegant, Butterfly, Olive, and Stork) themselves is something I found very appealing.

My Name Is Red employs several traits that are creative and clever, but the story doesn’t meet the sum of its parts. While each individual stylistic choice has its merits, they do not combine cohesively enough to make an enjoyable read a great book. While reading Pamuk’s work, I came to be under the impression that some portions of the novel could have been omitted to make more room for more crucial inclusions. The unnecessary bits, though, are still incredibly well written and weren’t, by any means, detrimental – only superfluous. The romantic side of the novel, that is otherwise exclusively a murder mystery with philosophical implications, seems tangent to the overarching plot other than the fact that it appears to be a tool to tie loose ends together.

As previously mentioned, one of the principle ideas in the novel is whether or not to embrace the different ideas unique to Eastern and Western thought in art and style, and the elevated notion of what qualifies something as a true and pure art or form. This was an interesting thing to keep in mind while reading the book, considering that I am an American reading an originally Turkish book, i.e. a Western reader of an Eastern text. This thought contributed significantly to how I value the work of translators in preserving the original flow, style, and the connotative diction of the original author.

“They depict what the eye sees just as the eye sees it. Indeed, they paint what they see, whereas we paint what we look at.”